Oh, Siena. A place caught between the jagged edge of Florence’s rising supremacy and the crumbling uncertainty of the plague. A city where, for a few extraordinary decades, paint—glorious, unruly, temperamental paint—became not just a medium but a language, a prayer, and a way of seeing. The Met’s exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350, feels like a forgotten letter from the past, an intimate conversation with artists who understood the very human business of beauty. And, my god, isn’t that the real allure of this exhibition? Not just the art, but the intimacy. The way the artists of Siena – Duccio, Simone Martini, the Lorenzetti brothers – painted grief, triumph, and devotion with the urgency of a lover’s first confession.

Oh, Siena. A place caught between the jagged edge of Florence’s rising supremacy and the crumbling uncertainty of the plague. A city where, for a few extraordinary decades, paint—glorious, unruly, temperamental paint—became not just a medium but a language, a prayer, and a way of seeing. The Met’s exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350, feels like a forgotten letter from the past, an intimate conversation with artists who understood the very human business of beauty. And, my god, isn’t that the real allure of this exhibition? Not just the art, but the intimacy. The way the artists of Siena – Duccio, Simone Martini, the Lorenzetti brothers – painted grief, triumph, and devotion with the urgency of a lover’s first confession.

It’s curious how often history forgets those who came before the flood. Florence, with its river, its money, its flourishing banking industry, always gets the credit for nurturing the Renaissance. But Siena—ah, Siena is the one we tend to overlook. Maybe it’s the stubbornness of its isolation or the tragic irony of its eventual downfall in the wake of the Black Death. For centuries, Sienese art has been considered a kind of introduction to something grander, a necessary prelude to the full-bodied realism that would burst forth from Florence. But if you take a moment, slow down, let the weight of the gold leaf and the shimmer of tempera sink in, you’ll realize that Siena wasn’t just the warm-up act. It was the rehearsal for the full, blazing orchestra of Western art.

The exhibition at The Met, with its staggering collection of over 100 works, lets you feel that. For the first time in America, you can witness the works that made Siena Siena—a city where angels did not flutter but flamed in their ineffable majesty, where the Virgin Mary was always, somehow, both a mother and a goddess, vulnerable and omnipotent all at once. The Sienese knew the power of paradox like no one else. And this show—painterly and intricate in ways that don’t let you look away—teaches you to know it too.

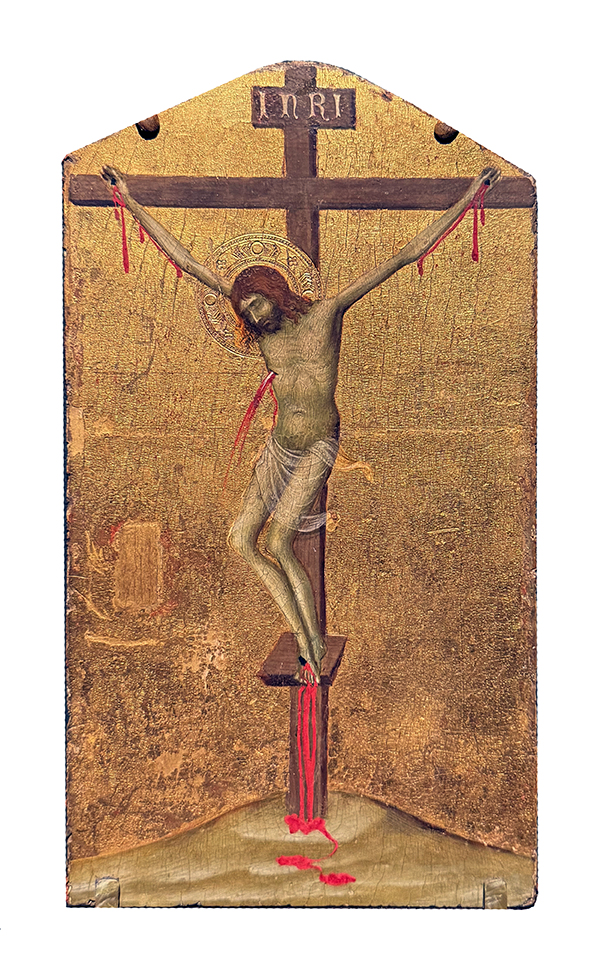

And yet, the most astonishing thing is not just what’s in the show, but how it feels. Duccio di Buoninsegna, with his maestà panels and sculptural altarpieces, wields a subtlety of touch that sneaks up on you. In his Crucifixion (ca. 1311-18), there’s a tangible weight to the figures, as if their very blood is sinking into the earth along with Christ’s. Duccio’s genius is that he paints gravity with such delicate force that you feel the pull in your bones. These figures are heavy, rooted, stuck in the mire of human emotion, yet they hover with a quiet grace. A woman to the left of the scene, holding the staggered Virgin Mary, seems poised on the edge of an impossible sorrow, smiling as though she could just as easily break into tears. That almost smile—almost standing—could be the signature of an entire city. The Sienese had a way of touching the ordinary that left you reeling, seeing emotions in the smallest, most exquisite gestures.

But there’s more to Siena than just melancholy, isn’t there? A brief, fleeting moment of triumph preceded the plague. The city was alive, absorbing the finest influences from all over—Islamic rugs, Scholastic philosophy, French metalwork—and turning them into something uniquely its own. Duccio’s Maestà altarpiece, painted for the cathedral, would set the stage for centuries of sacred art. And even as Florence rose, Siena’s painters took their place as prodigies in a rapidly shifting world, sending out their brushstrokes to places like Assisi, Avignon, and beyond. Pietro Lorenzetti swept through Italy, his paintings layering architecture and space in ways that seemed downright cinematic for their time. You see it in works like The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain, where the tiny, toy-like buildings beneath Christ’s feet seem to tremble with the knowledge that they might be crushed at any moment by the gargantuan presence of the Devil looming above. Siena had a taste for the dramatic, and the world had better watch out.

But then, disaster. The plague came, a great black curtain that fell over Europe, tearing cities apart. The world seemed to hold its breath—and half of Siena did not survive. The artists who had captured the sacred, the human, the miraculous—all of them perished in that foul year. Duccio was gone long before, but the Lorenzetti brothers died, and with them, an era of exquisite, highly stylized art, full of both tension and grace.

And it’s that very tension that the Sienese mastered, which, even in their quieter works, catches you off guard. Simone Martini, who once dazzled at the papal court in Avignon, could create something so strange and delicate that you couldn’t quite place it. Take Madonna del Latte (ca. 1325)—the baby Jesus, an odd contradiction, heavy yet weightless, poised in the most improbable of ways. The child sucks greedily at the Virgin’s breast while his eye holds yours in a glance so commanding it feels more like a verdict. Are we witnessing purity or sin? The Holy or the human? Both. The Sienese never felt the need to smooth out the paradoxes of life and faith, instead luxuriating in them, finding sophistication in their chaos. Vernon Lee, a critic of the late 19th century, would later call Sienese painting “the charm of the backwater,” but I think that’s a misreading. It wasn’t childishness; it was something much more dangerous: the full complexity of being human, unwrapped and unflinching.

But, as with any true love, there are quirks. Faces. The Sienese didn’t quite get faces the way later artists would. There’s a certain stylization to them, an archetypal calm that doesn’t always translate into real emotion. And yet, there’s something endearing about it, something that allows you to read the body language, the hands, the folds of cloth. In fact, you read these paintings—savoring the way a hand curls, the way an expression hovers just on the edge of something bigger. You’re invited to decode them, to wrestle with the questions they pose.

The last work in the exhibition, Simone Martini’s Christ Discovered in the Temple (1342), feels like an elegy. It marks the end of the era. There’s something about the intensity of those three faces—Mary’s pain, Joseph’s frustration, Christ’s defiance—that signals a shift, a new age in Western art. Gone are the tender contradictions, the awkward and subtle interplay of the sacred and the earthly. But, for me, I can’t help but miss the weirdness of it all, the way the Sienese never quite bothered to make things neat. The earthiness, the childlike wonder—it’s all so necessary.

So, if you’re in New York, take an afternoon, step into the Met, and surrender to the peculiar beauty of Siena’s rise and fall. You’ll find that the Sienese painters, who for too long have lingered in the shadows, are no longer the warm-up act to something greater. They are the thing itself—bold, strange, and more human than you might ever have expected. And who knows? You might just leave a little bit in love with them, too.

Discover more from Art Sôlido

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.