You enter the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue—the lions, as always, pretending not to look at you—and without quite realizing it, you’ve stepped into a studio. The Wachenheim Gallery transforms into Robert Motherwell’s workspace, where books and pigments mix like gin and vermouth—though with decidedly more ink.

You enter the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue—the lions, as always, pretending not to look at you—and without quite realizing it, you’ve stepped into a studio. The Wachenheim Gallery transforms into Robert Motherwell’s workspace, where books and pigments mix like gin and vermouth—though with decidedly more ink.

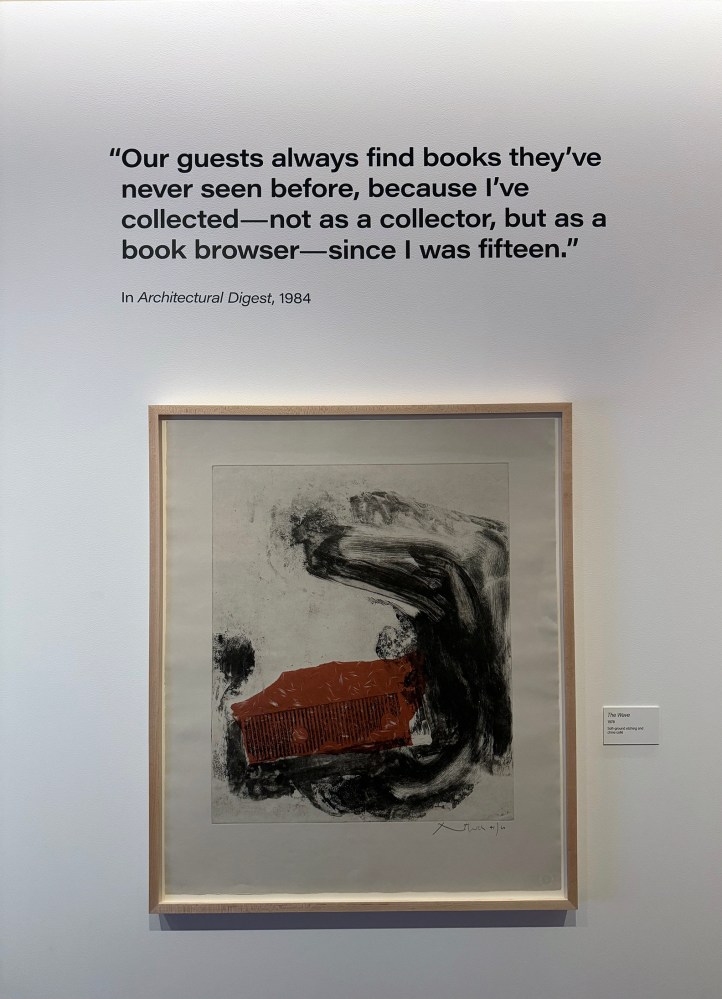

Robert Motherwell: At Home and in the Studio, curated with special tenderness by Clare Bell, isn’t one of those hushed, mausoleum-style retrospectives. No. This is something far more intimate: a slow exhale into the space where a man painted, read, scribbled, and underlined his way through modernism. It’s as if we’ve been allowed to sit in his Greenwich home while he’s out for a walk, the coffee still warm.

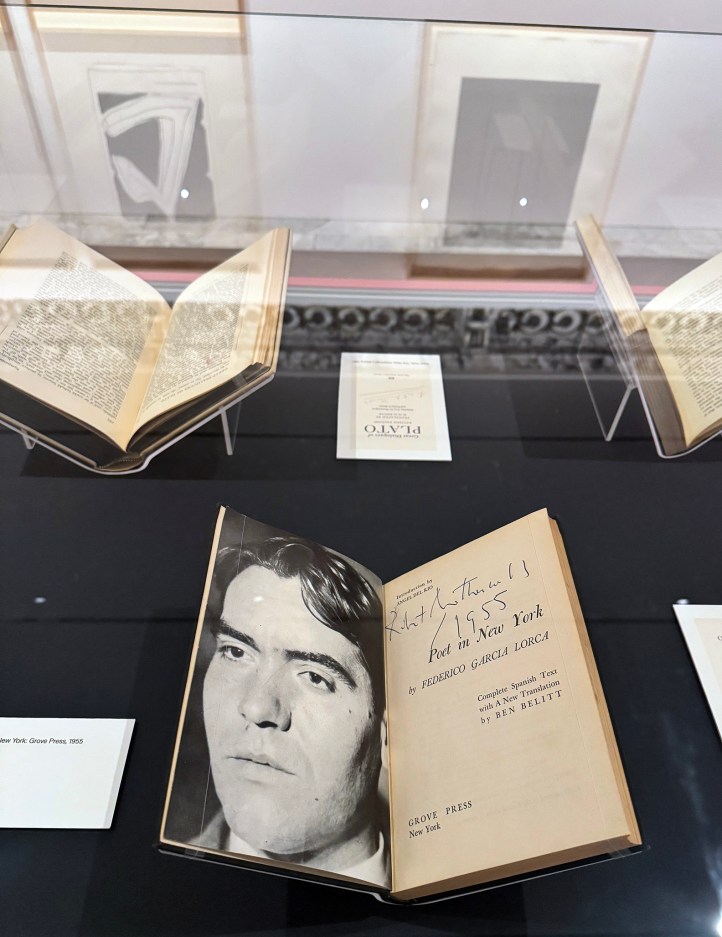

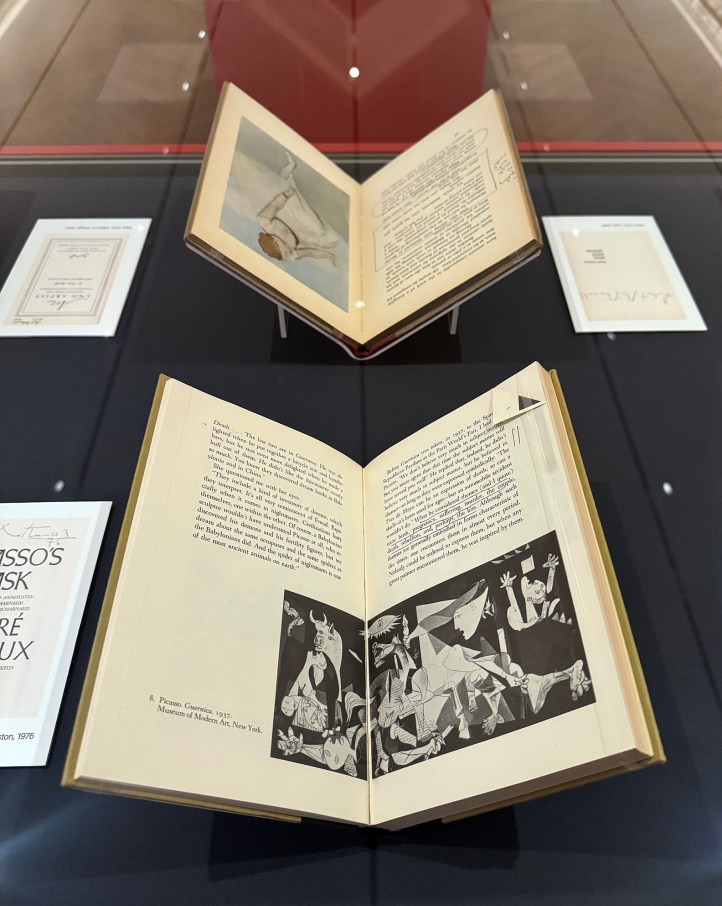

We’re not just shown his prints—though they are here in their brilliant emotional gravity, aquatints and screenprints pulsing with the hum of subconscious language. We’re given something even rarer: his books, his annotations, his marginalia. His thoughts-in-process. You get the sense that the brush never really left his hand, even while reading Poe or Mallarmé. That his pen was always ready to turn a sentence into a gesture, a paragraph into a shape.

And these were not decorative books. This wasn’t a library installed for show. No beige spines matching the curtains. No. Over 4,000 volumes, lived-in, marked up, chewed on intellectually. Poetry, philosophy, history—what a man carries through a life. His notebooks and underlinings are like second canvases. The same way a poet might annotate Lorca or Whitman, Motherwell reads to be undone. To be triggered into creation.

In one vitrine, you see a volume of Rimbaud, marked as if the page had to be rescued from drowning. Another corner holds “Dada Painters and Poets”, which he edited himself—back in 1944, when he was already conjuring bridges between Europe and America, between verse and violence, between war’s wreckage and art’s response. The Dada anthology, that strange bible of modern chaos, speaks volumes about where he stood: one foot in the literary avant-garde, the other in the paint-splattered studio.

He wasn’t just in conversation with visual artists; he was dining nightly with writers, mentally at least. And not just big ones—he let the language in, like light through the window. The reading was never passive. It was generative. Sometimes I think Motherwell painted as if he were trying to translate a poem he couldn’t quite finish.

There’s a particular melancholy in seeing the overlap of his worlds. The studio becomes a bookshelf, and the books become brushstrokes. The man is never only painting, never only reading. He’s feeling his way into the heart of something—not just aesthetics, but existence. The gesture, always, is a kind of question. What is human? What is remembered? What is forgotten?

The prints on view here—black, white, ochre, blood-red—don’t illustrate texts, but they pulse with the same urgency. Some look like torn pages from a dream. Others, like punctuation blown up to the size of protest. But always, there is thinking, deeply embedded in the work. The shapes may be abstract, but the emotion isn’t. You don’t need to know Hegel or Lorca to feel it. The art breathes on its own.

And then there’s the paradox of silence. So much of the show is quiet, contemplative. Like reading a letter never meant to be sent. You wander past the vitrines, read his notes in a looping, elegant hand, and it feels almost intrusive. And yet: he wanted us here. That’s the gift. This isn’t a museum of mourning—it’s a communion.

Standing in the Wachenheim Gallery, just steps from Bryant Park, the city breathing just beyond the marble, you begin to realize this show isn’t just about a man who read and painted. It’s about the in-between, that space between the page and the canvas, between solitude and expression. It’s about the studio of the mind. A life devoted to both line and language.

And so here we are, in the library, looking at an artist’s library. We are guests in his intellect, seated in a chair of imagination and critical inquiry. We are inside the room where literature and art made love and left behind something trembling.

Motherwell understood, as all great artists do, that to make something truly modern, you have to look backward with full heart. That Dada mattered. That poetry had blood in it. That printmaking was not a retreat but a sharpening. And that a painter could, in the same breath, be an editor—of ideas, of time, of silence.

This exhibition gives us something rare: not a monument, but a moment. A moment inside a man who read deeply, painted boldly, and lived always between gesture and thought.

Go. Before August 2nd. Go not like a scholar, but like a friend. Go to read his books with your eyes, and his art with your body.

And maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll hear his voice in the white space between prints.

Not shouting, but murmuring:

“This, too, was a kind of poem.”

Robert Motherwell: At Home and in the Studio en the New York Public Library, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building

Wachenheim Gallery Through August 2, 2025.

This exhibition is organized by The New York Public Library and curated by Clare Bell, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Associate Director for Art, Prints and Photographs.

Discover more from Art Sôlido

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.