Before arriving in America in 1933, Albers had been teaching at the Bauhaus, where precision was a moral value and materials were treated as language. In 1928 he experimented with sandblasting and stenciling on glass, learning that geometry could behave like light. When the school closed under political pressure, he carried that discipline across the Atlantic to Black Mountain College, where the American landscape entered his thinking—not as nature, but as structure.

Before arriving in America in 1933, Albers had been teaching at the Bauhaus, where precision was a moral value and materials were treated as language. In 1928 he experimented with sandblasting and stenciling on glass, learning that geometry could behave like light. When the school closed under political pressure, he carried that discipline across the Atlantic to Black Mountain College, where the American landscape entered his thinking—not as nature, but as structure.

New York fascinated him immediately.

Not its monuments.

Its order.

The avenues counted. The blocks repeated. Windows echoed windows. The city was not chaos—it was rhythm.

He began developing compositions he simply called City.

Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

The mural that commuters built with their footsteps

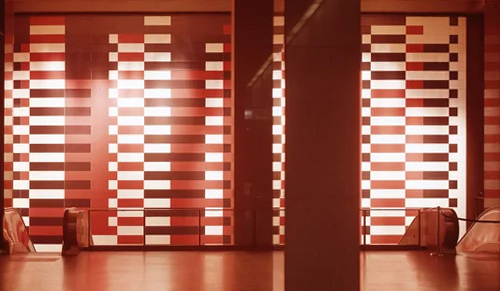

In 1963, architect Walter Gropius commissioned a monumental version for the Pan Am Building lobby, directly above the passage into Grand Central. The work consisted of 486 Formica panels, industrial laminate normally used for kitchen counters. Albers elevated the ordinary into architecture.

He called it his “homage to the city of New York.”

The location mattered. This was not a museum painting. It was a civic experience. Nearly a quarter-million people a day walked under it—secretly completing the artwork by animating it.

The mural translated the city into pure relationships:

verticals = towers

horizontals = streets

repetition = movement

color = traffic

New York became an abstraction of itself.

Disappearance

In 2000 the building changed ownership. Renovations followed. The mural was removed and stored. Later inspections revealed asbestos in the original panels, making preservation impossible. Most of the material was discarded.

The city barely noticed at first—yet something intangible had vanished. The lobby felt larger but emptier, as if its memory had been erased. Architecture without its artwork became merely real estate.

Public protest grew. Architects, historians, and commuters remembered they had been living with a masterpiece they never formally visited.

Resurrection

Nearly twenty years later, during the building’s restoration, the mural was reconstructed using Albers’s exact specifications preserved by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. New panels were fabricated, colors matched precisely, and the wall itself expanded to receive the work properly.

In 2019 it returned to its original place.

The grid again greeted the morning rush.

White travertine columns now frame it, light washes across the red planes, and the geometry breathes. It does not look nostalgic—it looks contemporary, because cities never stop being modern.

What the mural really shows

The work is often described as abstract, but abstraction is the wrong word. It is translation.

Albers did not paint buildings; he painted perception:

You do not remember every skyscraper.

You remember the pattern they leave in your mind.

Standing beneath it, you realize the mural behaves like the city itself. From far away: order. Up close: countless differences. Move sideways and the relationships change—just like walking along Park Avenue at sunset when windows ignite one by one.

The piece is less about color than about coexistence. Every rectangle holds its place without dominating the others. A quiet urban ethics.

A public artwork, not decoration

Most art waits for viewers. This one intercepts them.

No ticket, no opening hours, no intention required. The painting enters daily life the way weather does. A commuter late for a train still experiences it—even unconsciously—and carries a trace of structure into a chaotic day.

That was the radical idea: art embedded in routine.

Thousands pass under it without looking, yet they look better afterwards.

And perhaps that is the true portrait of Manhattan—not its skyline, but the invisible discipline that keeps millions moving together without touching.

A painting you cross rather than face.

A museum you commute through.

A city translated into balance.

Discover more from Art Sôlido

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.