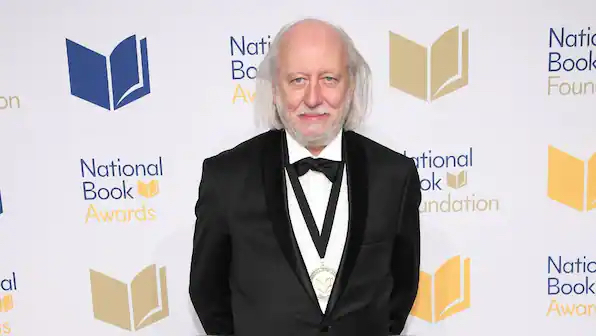

I was sipping an espresso in a West Village café when the news flashed on my phone: Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy praised his “compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.” In that moment—amid the clatter of dishes and the honking taxis outside—I felt the distance between New York and Havana collapse. A voice that had once reached me from behind the Iron Curtain was now being honored on the world stage.

I was sipping an espresso in a West Village café when the news flashed on my phone: Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy praised his “compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.” In that moment—amid the clatter of dishes and the honking taxis outside—I felt the distance between New York and Havana collapse. A voice that had once reached me from behind the Iron Curtain was now being honored on the world stage.

A Voice from Communist Shadows

Growing up in Aguada de Pasajeros, a small town in Cuba under a communist regime, I learned early the power of forbidden literature. Books were whispers of freedom, passed hand-to-hand under flickering bulbs. Those of us who lived under communism found writers like Krasznahorkai hidden in the shadows of censorship, and we read them with a mix of fear and reverence. His pages carried truths our officials preferred to silence. Reading Krasznahorkai gave us certainty – a sense that someone, somewhere understood the despair and absurdity we lived.

For young people who never experienced communism yet sometimes romanticize it, I have a simple suggestion: read Sátántangó (1985). His debut novel—bleak, mesmerizing—predicted the regime’s downfall a few years before it happened — a story of destitute villagers lured into ruin by a false messiah. Terrifying, liberating, unforgettable. We turned its pages in secret, heart pounding, as if the very act of reading were an act of rebellion. Today, I smile knowing that this once-forbidden fruit is celebrated by the Nobel Committee as a masterpiece.

Master of the Apocalypse

Who is this Hungarian voice that spoke so powerfully to those of us so far away?

The Nobel Committee calls Krasznahorkai “a great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, characterized by absurdism and grotesque excess.” Heir to Kafka’s dark vision, Krasznahorkai transmutes madness into art. Susan Sontag once called him “the contemporary Hungarian master of apocalypse who inspires comparison with Gogol and Melville.” Grand words, but apt ones. His work has a hypnotic pull. “He is a hypnotic writer,” says his translator George Szirtes, “He draws you in until the world he conjures echoes and echoes inside you, until it’s your own vision of order and chaos.”

Krasznahorkai’s sentences bend language to its breaking point. He called his method “reality examined to the point of madness.” His paragraphs run for pages, his rhythm unbroken. Szirtes likened his prose to “a slow lava-flow of narrative, a vast black river of type.” Reading him is like wading into a flood: at first overwhelming, then eerily immersive. You surrender to the current or you don’t survive the book. Demanding, obsessive, uncompromising – but for those who crave literature that pushes the boundaries of thought, his novels offer purification. They remind us there can be beauty in hell.

Epic of Melancholy and Resistance

Born in 1954 in Gyula, Hungary, into a middle-class Jewish family, Krasznahorkai lived through the full claustrophobia of communism. When he left for West Berlin in 1987, freedom struck him like oxygen. He wandered through Germany, China, and Japan, gathering the fragments that would become his fiction.

In the 1990s, he lived for a time in Allen Ginsberg’s East Village apartment, not far from where I’m writing this. Krasznahorkai speaks English with a seductive Mitteleuropean inflection, softened by the occasional American accent — a trace of those New York years. I like to imagine that quiet Hungarian craftsman walking down Second Avenue with a notebook in his pocket, absorbing the chaos and beauty of the city.

All these experiences sharpened his artistic gaze. As Academy member Steve Sem-Sandberg observed, Krasznahorkai’s vision is “entirely free of illusion”—he sees through “the fragility of the social order,” yet holds an unwavering faith in the power of art. It’s this blend of clear-eyed pessimism and artistic devotion that fuels his apocalyptic storytelling.

His novels are soaked in dystopian gloom and dark humor.

Sátántangó, as I’ve said, unfolds on a rain-soaked collective farm—twelve chapters swinging forward and back like the steps of a doomed tango. Béla Tarr’s 1994 film adaptation—seven hours long, austere and hypnotic—remains a monument of cinematic endurance. His next great novel, The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), brings a circus with a stuffed whale and a disfigured prophet to a provincial town teetering on collapse. Ellen Mattson of the Academy calls it “wonderfully dark and darkly funny.” Again Béla Tarr turned it into Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), with images of mobs and muted violence that still haunt me.

Then came War and War (1999): an archivist unravels in New York while trying to upload a sacred manuscript before killing himself. James Wood of The New Yorker called it “one of the most profoundly unsettling experiences I have ever had as a reader.” By the final page, I too felt stripped bare, as if I’d lived another man’s breakdown and survived.

Despite the darkness, Krasznahorkai’s work contains a fragile thread of hope — the conviction that art itself is redemption. In his 2008 book Seiobo There Below, he follows a white heron waiting motionless in a Kyoto river, a symbol of the artist’s stillness amid chaos. Academy member Anders Olsson calls the novel “magnificent,” finding in it “a finely tuned sense of darkness” and the glimmer of transcendence. It’s as if the “master of apocalypse” went searching for serenity in Asia—and, miraculously, found it.

Four Doorways into Krasznahorkai’s World

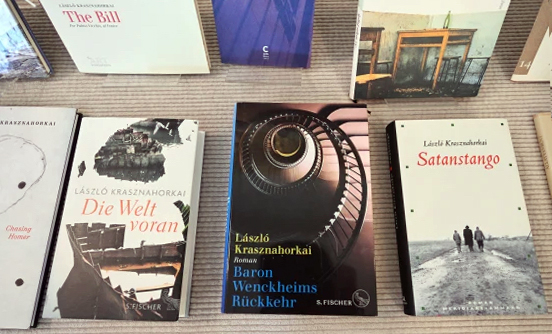

Sátántangó (1985):

A debut novel unlike any other, writes Sem-Sandberg. On the Hungarian plain, con-men Irimiás and Petrina lead villagers into an “apocalyptic dance with infernal consequences.” Forty years on, it remains a virtuoso first step in a visionary career.

The Melancholy of Resistance (1989):

A small town slides into nightmare as chaos spreads from a traveling circus. “You have to act even if there is no point to your actions,” Mattson notes. A timeless fable of disorder and dark comedy.

Seiobo There Below (2008):

Seventeen episodes meditating on art and impermanence—from Kyoto to Florence.

A white heron waiting in a river becomes the emblem of the artist: invisible, patient, eternal.

Herscht 07769 (2021):

In a small German town, paranoia and myth collide. Florian Herscht, a gentle giant, is swept into underground movements as Bach’s music drifts through the pages. Anna-Karin Palm calls it “musically flowing, lively prose.”

Each of these novels is a different portal—from village apocalypse to global meditation on beauty. Whichever you choose, you won’t leave unchanged.

A Nobel for the Unquiet Voices

The café has emptied; rain streaks the big windows. I catch my reflection—a Cuban-born writer far from home, thinking of how a Hungarian novel about an abandoned farm once kept my spirit alive under censorship.

Literature travels in mysterious ways. Krasznahorkai wrote from behind the Iron Curtain, yet his words crossed the sugarcane curtain to reach me. His Nobel feels personal—it vindicates the faith of all of us who clung to art in dark times, who believed in having a voice even from afar.

Krasznahorkai, now 71, is the second Hungarian Nobel laureate after Imre Kertész. He once thanked Kafka, Jimi Hendrix, and the city of Kyoto for shaping his imagination—an improbable trinity that somehow makes perfect sense.

Today, that voice rings from Stockholm to New York to Havana. In all its bleakness, it still “reaffirms the power of art.” I step back into the drizzle thinking: the world is full of apocalyptic terrors—wars, tyrannies, disinformation—but here is a writer who stared into that abyss and found meaning. Art survives. Voices carry. Even in hell, there is a beauty that can save us.

Discover more from Art Sôlido

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.